Whitehurst & Son sundial (1812)

Sundial in Derby Museum |

|

| Material | bronze |

|---|---|

| Created | 1812 |

| Present location | Derby Museum, England |

The Whitehurst & Son Sundial was produced in Derby in 1812 by the nephew of John Whitehurst.[1] It is now in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery. It is a fine example of a precision sundial telling local apparent time with a scale to convert this to local mean time. It is accurate to the nearest minute.

Contents |

Manufacturer

The Whitehurst family was known in Derby as eminent mechanics. John Whitehurst (1713–1788) was born in Congleton, but came to Derby where he entered business as a watch and clock maker. He moved to London when appointed to the post of Inspector of Weights. His nephew continued the business under the name of Whitehurst & Son. The family business was known for their turret clocks.[1]

Construction

Sundial construction is based on understanding the geometry of the solar system, and particularly how the sun will cast a shadow onto a flat surface, in this case a horizontal surface. Each day over a yearly cycle the shadow will be different from the day before, and the shadow is specific to the location of the dial, particularly its latitude. The dial is designed to tell local apparent time so the longitude is not significant. By this we mean that noon will be at the point when the sun is highest in sky and due south, standard time would be when the sun was due south at another point such as the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Derby is at 1° 28′ 46.2″ West of Greenwich [2], so the sun is approximately 5 mins and 52.05 s later in reaching noon. The other point to consider when telling the time is that as the earth moves around the sun in a slight ellipse, day length varies slightly giving a cumulative difference from the average, of up to 16 minutes in November and February,[3] this, with another correction, is known as the equation of time and was really irrelevant until people started comparing sundials with mechanical clocks, which must either ignore the consequences or be re balanced each day to make them correspond with the natural cycle. They measure average time or local mean time. Railways timetabling demanded a fixed noon and fixed day leading to the adoption of Greenwich Mean Time. The local Midland Railway had adopted Greenwich Mean Time by January 1848.[4]

This particular bronze sundial is marked "Whitehurst and Son/Derby/1812" and is thought to have been made for George Benson Strutt (who was the younger brother of the cotton spinner William Strutt), for his home Bridge Hill House, in Belper.[5][6] This has the precise location of 53° 1′ 49.08″ north, and 1° 29′ 26.88″ West of Greenwich,[7] which is slightly different from those of Derby, at 52° 55′ 00″ north, [2], a difference of 6′ 49″. The Longitude is almost identical, and gives only a 2 second time difference.

The Gnomon

This dial is stoutly made, with a thick gnomon, one edge of gnomon is the style [8] which throws the shadow before noon, and the other edge is the style which throws the shadow after noon. The dial plate is not made up of one complete circle, but two semicircles separated by the thickness of the style. In this design of sundial, the angle of the style to the dial plate is exactly the same as latitude, which is 53° 1′ 49″ the latitude of the Bridge Hill House. The dial plate will be perfectly horizontal, slight adjustments for latitude can be made were the dial moved by shimmying up the dial plate by the change in degree, from the horizontal.[9] As the dial is now 0° 6′ 49″, or about 1/10th of a degree south- the nose of the gnomon needs to be raised by that amount.

The dial plate

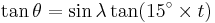

In the horizontal sundial (also called a garden sundial), the plane that receives the shadow is aligned horizontally, rather than being perpendicular to the style as in the equatorial dial.[10][11][12] Hence, the line of shadow does not rotate uniformly on the dial face; rather, the hour lines are spaced according to a calculation. [13][14] The dial plate is precision engraved, the hour lines having been calculated using the formula:

where λ is the sundial's geographical latitude (and the angle the style makes with horizontal), θ is the angle between a given hour-line and the noon hour-line (which always points towards true North) on the plane, and t is the number of hours before or after noon.

The Maths

For each of the hours 1 to 6, the formula is calculated. For instance at 3 hours after noon, we substitute the numbers 53.03 and 3 into the formula This generates these results

-

A dial for Belper 53.03 One hour 11.791779 Two hours 24.219060 Three hours 37.922412 Four hours 53.460042 Five hours 71.020970 Six hours 90.000000

The hours before noon are exactly the same, the dial is symmetrical, the other lines are mirror images of those above- 2 way symmetry. In the same manner, the half hours and the minute lines would be calculated. As noon lies exactly on the north-south line, and not 5' and 54" to one side we can tell that this dial is telling Belper time and not Greenwich time.[15]

Equation of Time

Significantly, on the plate we can see a pair of scales that help the observer make the equation of time correction. One scale gives the date in months and days while along side of it another engraved with the minutes on that day that the watch would be running faster or slower. Here it is labeled "Watch Slower, Watch Faster. The 15th April is one day when no conversion needs to be made.[16] This dial can be used both to read solar time shown by sundials and also the mean time that is favoured by clocks[17] , with the practical purpose that observers can use the dial to calibrate their pocket watches, which in 1812 would not always run true. By 1820 watches manufacture had improved:the Lever escapement had become universally adopted and frequent calibration was no longer needed.

Other Commissions

Another Whitehurst sundial dated around 1800 sold for £1850 in 2005 in Derby.[18]

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ a b Glover, Stephen (1929). Noble, Thomas. ed. History of the County of Derby. Derby: Stephen Glover. pp. 599. http://books.google.com/books?id=nqNCAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA599&lpg=PA599&dq=Derby+Whitehurst&source=bl&ots=JCVIe8A9JA&sig=EEvx6XdgaQMDv0ReR2D2V8q55eI&hl=en&ei=u3yoTe_SOYGy8QO77JCnBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCcQ6AEwAjgU#v=onepage&q=Derby%20Whitehurst&f=false. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ a b "Current local time in Derby". timeanddate.com. http://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/city.html?n=1325. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ Waugh 1973, pp. 8,9,10,31

- ^ Peter E Davies. "Railway Time". GreenwichMeanTime.com. http://wwp.greenwichmeantime.com/info/railway.htm. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "Sundial by John Whitehurst & Sons, 1812". flickr. http://www.flickr.com/photos/climatechangeem/4863532430/sizes/o/. Retrieved 2011-06-01. - Museum label

- ^ "Bridge Hill House, Belper, Derbyshire, UK.". http://www.knight-gkla.supanet.com/bridge-hill-house.htm. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ Google Maps

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 72

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 47

- ^ Rohr 1966, pp. 49,55

- ^ Waugh 1973, pp. 35,51

- ^ Mayall & Mayall 1994, pp. 56,99,144

- ^ Rohr 1966, p. 52

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 45

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 12

- ^ Mayall & Mayall 1938, p. 70.

- ^ Waugh 1973, p. 9

- ^ "Details of Lot 1913". Bamfords Auction house. 2005-09-13. http://www.bamfords-auctions.co.uk/BidCat/detail.asp?SaleRef=FASEPT05&LotRef=1913. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- Bibliography

- Mayall RN, Mayall MW (1938). Sundials: Their Construction and Use (3rd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Sky Publishing. ISBN 0-933346-71-9.

- Rohr RRJ (1996). Sundials: History, Theory, and Practice (translated by G. Godin ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-29139-1. Slightly amended reprint of the 1970 translation published by University of Toronto Press (Toronto). The original was published in 1965 under the title Les Cadrans solaires by Gauthier-Villars (Montrouge, France).

- Waugh AE (1973). Sundials: Their Theory and Construction. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22947-5.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||